Lucky, Camello and Malborina, 3 of the main characters in Rasputin Barxotka.

Why I Read: Rasputin Barxotka

Another great “Why I Read” review by contributor Neil Kapit, creator of the webcomic Ruby Nation.

He explains why he reads and enjoys Rasputin Barxotka, by Vas Littlecrow Wojtanowicz.

Synopsis:

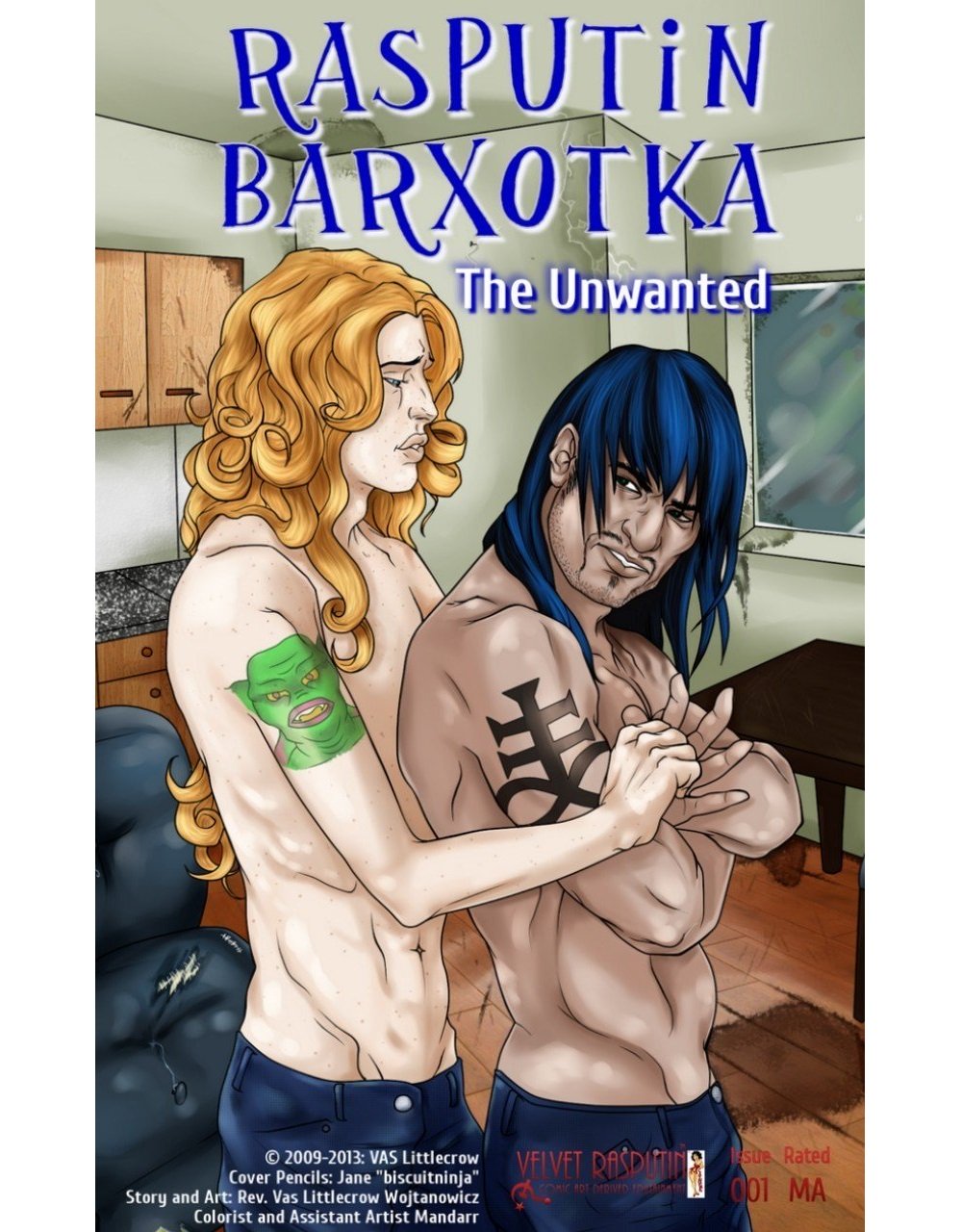

Rasputin Barxotka is an epic, sprawling historical graphic novel about several LGBTI characters in early 1990’s Russia (immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union), written and illustrated by Vas Littlecrow Wojtancowicz, with assistance by Mandarr and a cover by Jane “biscuitninja”. The cast is large and the story weaves between different characters’ subplots, but there are a few characters who share a protagonist role. The first book weaves between the stories of Sasha, a girl who discovers she’s intersexed during puberty; Lucky, a Romani man with a strong self-loathing streak; and Camello, formerly Lucky’s young lover and currently holding a blazing torch for his ex.

Disclaimer: The comic is gloriously NSFW, with a lot of sex (especially gay sex) between the cast members. Though the comic is explicit, it is not pornographic; rather, author Wojtankowicz aims to show the extremes of the characters’ personalities and situations, as they all live on the margins of the larger society, away from the protection of the law, and often at the mercy of opportunists and predators.

How I Found It:

I originally found Rasputin Barxotka and its counterpart Rasputin Catamite through the Webcomic Underdogs group, shortly after I joined. Through the site I found Kindle Editions of the comics; for the sake of this review, I’m focusing on the first volume, and plan to do a follow-up detailing the overall saga.

What I Like:

Rasputin Barxotka is not an easy comic to read. Not only does the NSFW have the potential to alienate readers, but the characters themselves are monstrously flawed people. The vast majority of people you see in this comic are impulsive, violent, and even abusive to those they care about. Characters who talk about assaulting each other like it’s just another relationship issue are inherently unsympathetic; however, the brilliance of Barxotka is how it invites us to sympathize with such people.

There are no happy, stable people in Barxotka. They live on the fringes of society, where happiness and stability are inherently impossible. To the world at large, these people are so deviant that they might as well not exist, and would certainly be disappeared by the government if they stepped too far into the public light. Amongst their own cultures, they are the unmentionables, a pressure that is felt internally and leads to deep self-loathing. Lucky is a quintessential example of this kind of outsider; he was raised in Roma culture, a group subject to extreme persecution while having some of their own taboos and bigotries. He has to balance being as successful and upstanding in public as he can (to minimize the prejudice against him, Lucky brings up his Spanish heritage most often), while rampantly sleeping around with “forbidden” people indulging his own repressed energies. Lucky eventually marries a woman named Marlborina who he actually loves, but his trail of past affairs can’t be forgotten so easily (including by himself).

At the same time, while the characters often speak and act awfully towards each other, they don’t hate each other. They don’t quite like each other either, but there’s definite love, or at least attachment that keeps them in each others’ lives. Camello stays around Lucky and Maldronia, and neither is keen to cast him completely out of their worlds. It’s the kind of bond you have with someone who’s seen you at your absolute worst, and vice versa. You may have grievances against them, but they understand you best because they’ve seen the parts of you that you militantly hide from the rest of the world, and they’re okay with it. In the world of Rasputin (Barxotka and Catamite), deviance is just as much a fact of life as difference, and just as impossible to remove from the human experience. It’s a bittersweet message, but far deeper and more relevant than the shallow and useless “Just be yourself” messages that pollute American pop culture without actually helping anyone who feels different.

The art delivers this message perfectly. Similar to the story, Rasputin Barxotka’s art is an acquired taste, with cartoony characters, minimal details, and thick linework. The stylization and exaggeration is jarring to those raised on more representational comic art, and it makes the sex scenes even rougher (not to mention less titillating). Ironically, the deliberately primitive art style also serves to make the story far more realistic. These characters are rough around the edges, because their world has made them that way. The art literally conveys them with warts and all, and is far more emotionally affecting for it.

What Could Be Done Better:

While I’ve spoken of Rasputin Barxotka as a difficult comic to read, that’s not an indictment of its quality; it’s alienating because it shows a part of the world with extremes that most of us have been sheltered from. Wojtancowicz comes from a truly cosmopolitan background and brings this to her work with brilliant artistic flair. If Rasputin Barxotka is problematic, that’s because life is problematic, prejudice is problematic, and oppression of sexual identity is problematic. This comic is a mirror which reflects what we don’t want to hear.

In terms of formal quality, my only complaint involves the dialogue. There is a tendency for characters to speak a lot about their background, dumping information about the history and setting. It’s likely that most readers won’t understand the historical context, but putting that information directly in the characters’ mouths can come across as stilted. It works better when annotated separately, such as with the site’s glossary.

Since I’m reviewing with the Kindle Edition in mind, I must also critique the use of filler pages and mid-story diversions (such as moving into the author’s autobiographical strips) in this version. While Kindle comics have the advantage of a much more fluid read (due to lack of interruption by slow internet connections or advertisements), with that comes the expectation that you’ll be getting a whole, uninterrupted story. This is not a deal-breaker and I plan to pay for the other Kindle Editions, but it’s still a slight irritant.

Final Thoughts:

I had difficulty writing this review because I couldn’t easily categorize Rasputin Barxotka. It is something so unique, hard-edged, and affecting that it defies even the multiple genres in which it might fall. It is not for the squeamish, but it is something that deftly shows a part of the world and the human spectrum of emotions and sexuality that most might not (but should) consider. Both the comic itself and the Kindle versions are strongly recommended.